Surf Panama, Chapter V

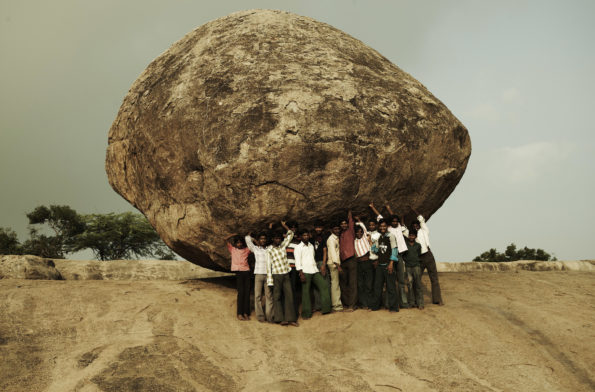

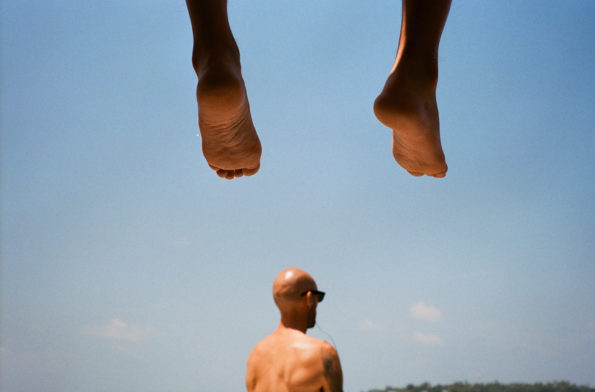

Spare time

Getting back to your roots

thousands miles from home

There are a few hours per day you just can’t surf: the sun is so bright it leaves no shadow, the heat is grueling and the ocean is having some rest. Like in a pre-industrial civilization, your time is ruled by the sun, the moon, the tides. Although you are forced to leave your board at home, you feel the wonderful sensation of having spare time. You rediscover the infantile sense of non-urgency: you can take a nap, have some food, read a book, you can even play and discover the environment around you.

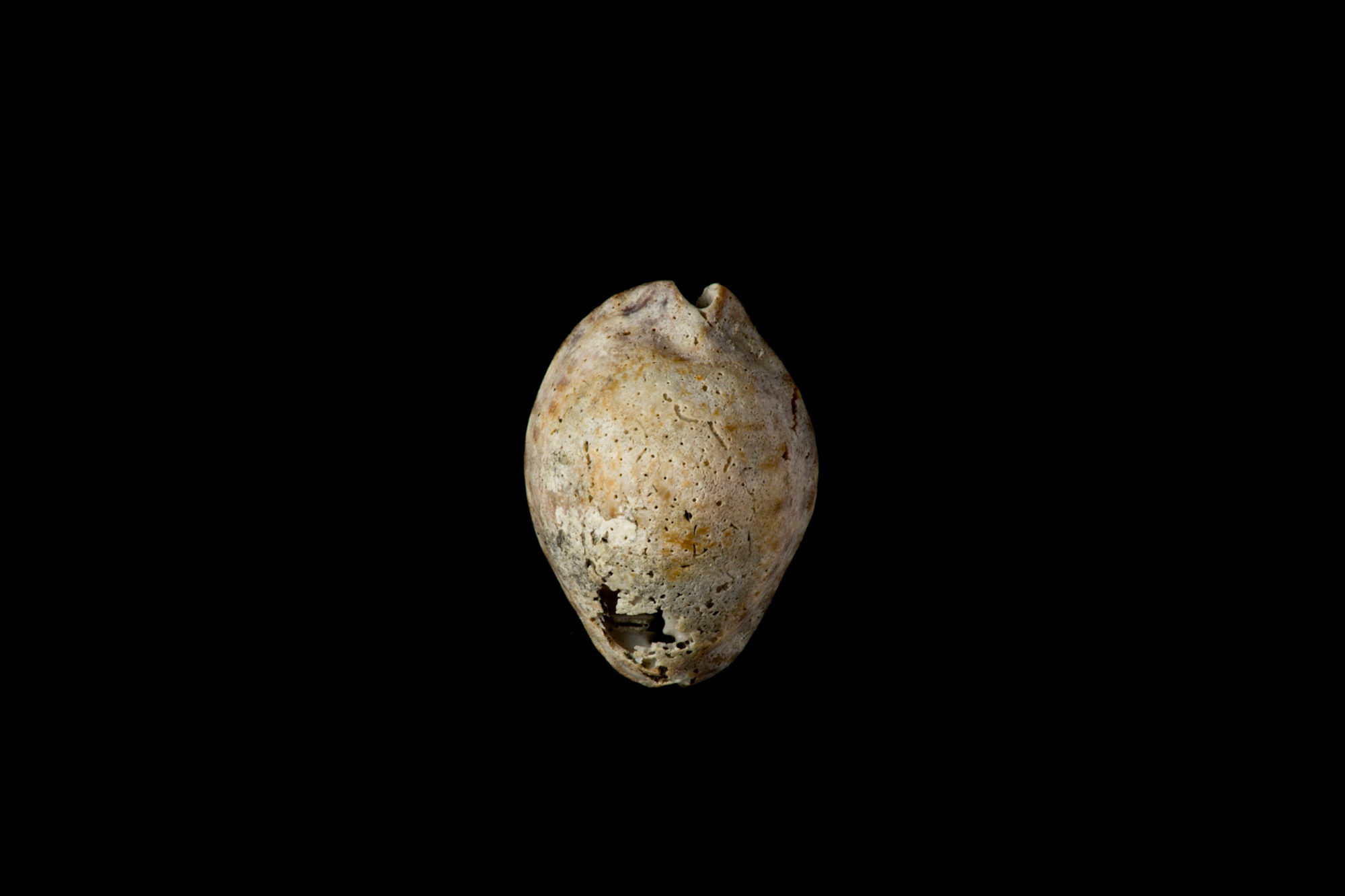

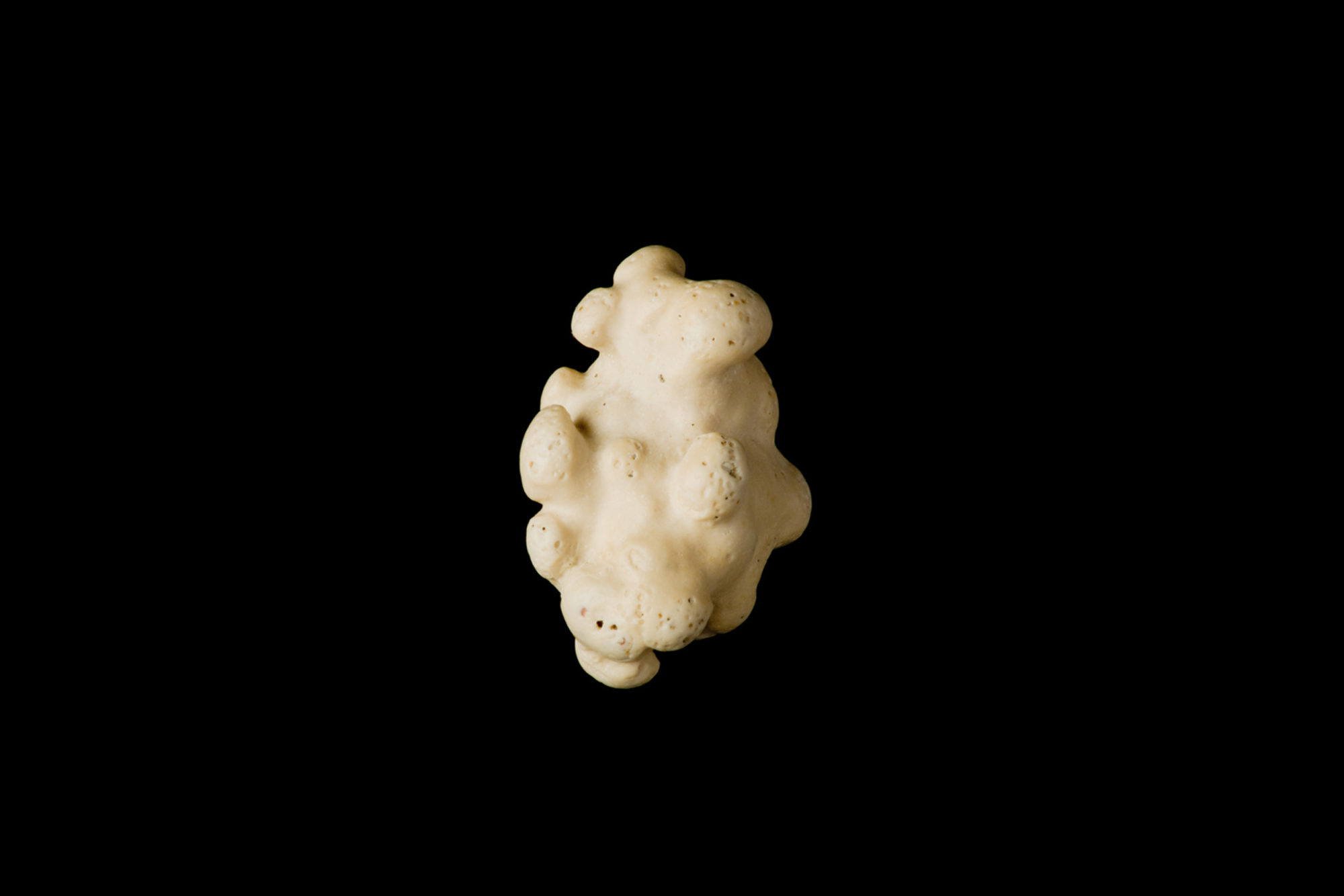

I don’t know why, but we started playing at being explorers. We grabbed a machete, we penetrated the mangrove forest and actually began patrolling the place. It’d begun as a game, but it turned into a half-serious thing. We spent hours discovering plants and spotting animals, collecting seeds, beautifully shaped-stones, little branches from the trees. We laid them out in order, from the smaller ones to the bigger ones, then we took pictures of them. But why?

Like probably most of the people, we realized that this was something we were actually doing a lot in our childhood. We recalled afterwards the intrinsic satisfaction and the fulfillment it used to give us. Collecting objects is a natural human activity. This hunting and gathering need seems to be strongly rooted in our “humanness”. In their first phase of their life, children collect what they could find in their immediate environment: they accumulate little rocks, buttons, stamps, bottles of sand, pictures, small seashells, pens and pencils, pieces of wood.

After all, it is exactly like kids’ innate curiosity and trembling desire to know. As you leave the city behind and go back to the outdoor, it’s fascinating to find yourself doing the same thing after all those years. Unlike the real explorers and researchers, we weren’t seeking scientific results. We were looking for an aesthetic content, for simple beauty.

Photo. Dizy Díaz

Words. Vincenzo Angileri / Eldorado

Albert Folch

Surfer and Art director

Dizy Díaz

Surfer and Photographer

@albertfolchrubio

@albertfolchrubio @albertfolchrubio

@albertfolchrubio