An African Folktale, Chapter II

Living your own tale

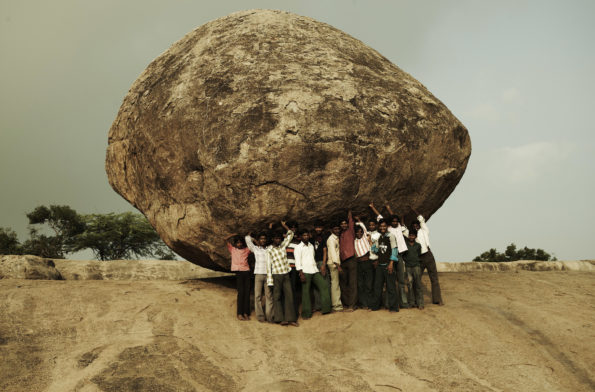

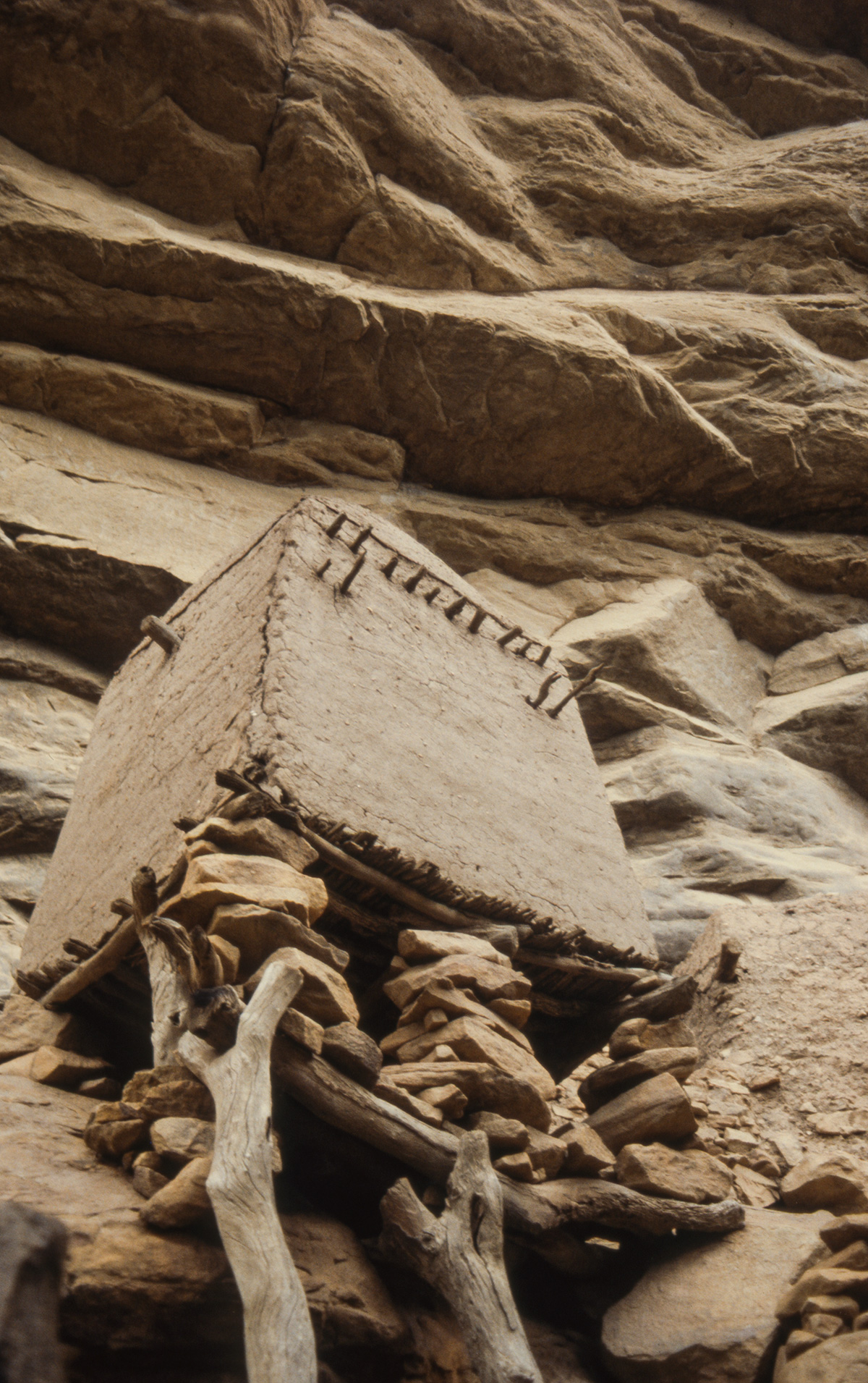

An isolated plateau, a cliff, a waterfall, a dwelling rising from the mud: here, the Dogons protected their culture from the rest of the world.

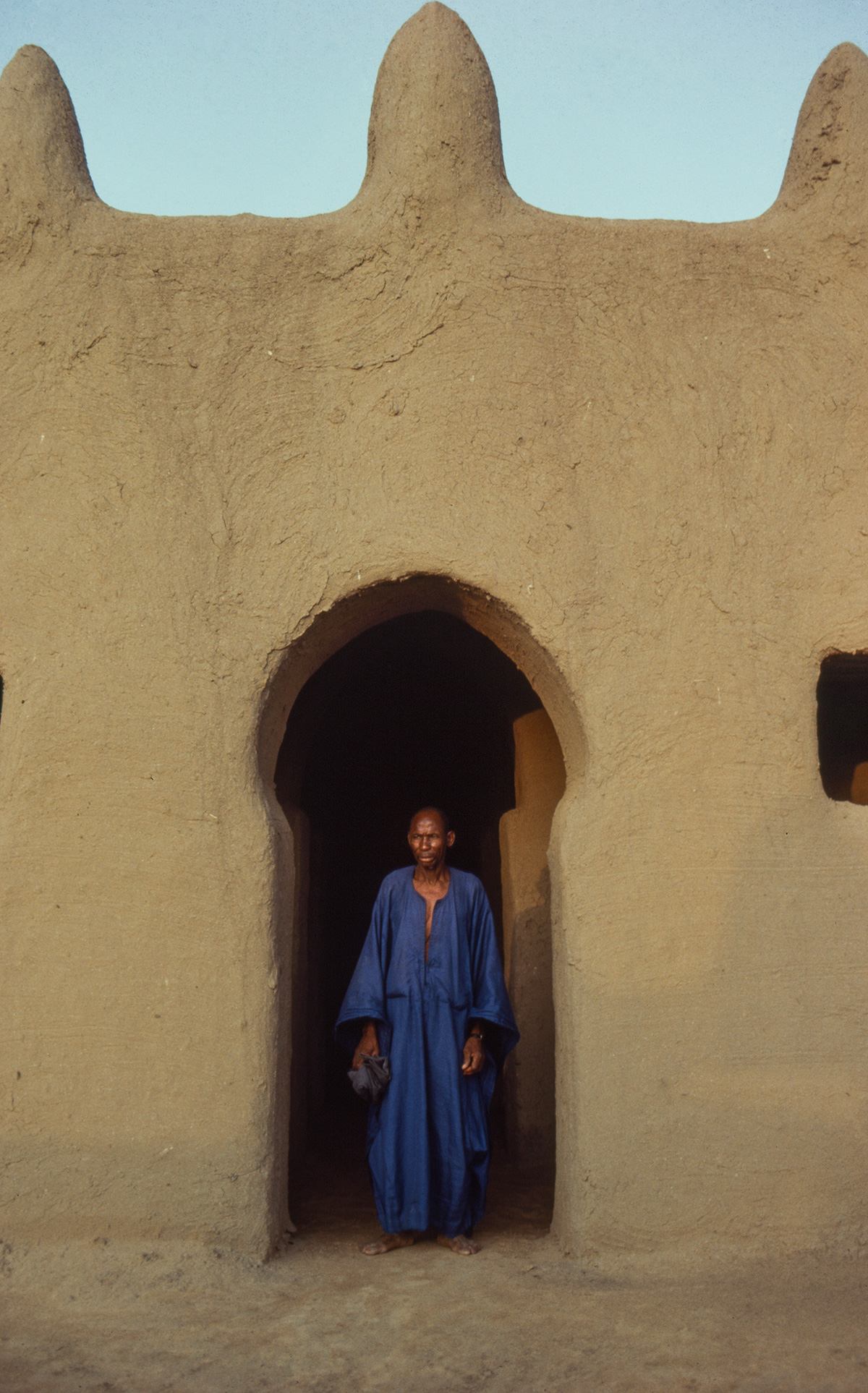

Beauty of Mud

In such a vast and open space, the Dogon village appeared cluttered. Walking through its alleyways we noticed that the buildings all have their particular significance. The pointed roofs I could see were granaries, and the more pointed, the greater the prosperity. I observed other granaries, without points, too. Months later I learned they were the female granaries, as in Dogon society women and men are economically independent.

Minarets, houses, and granaries melted beautifully into the landscape.

The Toguna is a building only for men. It’s the place where men gather to discuss and make decisions. We spent some evenings there, us, sitting alongside the men of the village, and me, particularly, surprised at how low the roof seemed to be constructed. I decided to ask about it. They told me, “If a debate gets heated, none of us can get angry and stand upright or his head will hit the ceiling”. They all laughed.

An ancient knowledge that comes from the stars

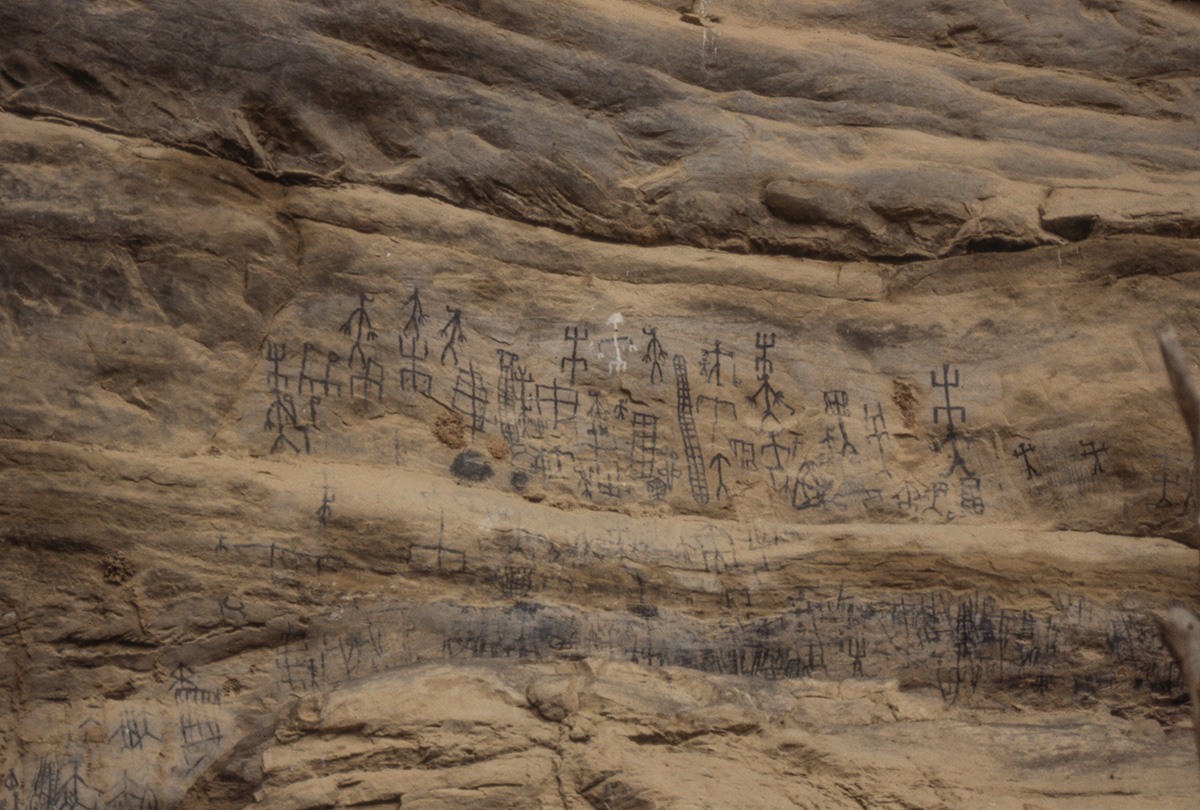

Far from paved roads, the territory has protected the Dogons for countless centuries in the face of invaders and neighboring influences. They have managed to keep their astronomic knowledge, their culture, artistic expression, and complex belief system hidden from the rest of the world. This way, it has remained mostly unchanged for thousands of years. We know from wall drawings and ancient rituals that Dogon priests have known for centuries that the Sirius star has a companion, invisible to the human eye. The tribe claims that the secret twin of the most brilliant star is composed by a mysterious and dense metal. They first noticed this star in the 19th century, way ahead of modern discoveries.

For centuries, the Dogons have known the existence of stars which modern telescopes were only able to observe in the last 150 years.

I could barely sense this depth when I was there. I had the constant sensation of being outside the boundaries of the known. The feeling of an embracing and beautiful isolation was intense. My body felt different.

We meet the Hogon again

We were near the Toguna again. Children were playing with us, touching our hair, as we once again attempted to share some words with one of the elders. Suddenly, a man arrived, asking us if one of us was a doctor. Neither of us were, but we wanted to be of help anyway. “Come with me”, he said. He brought us to a beautiful, tidy house. It was the Hogon’s, and his legs were covered in wounds and sores. As my friend Josep leaned over to him, the man behind screamed “No! You cannot touch him! Only his son can”. The son arrived. “Wait”, he said, “I need to change clothes”. He took off his old t-shirt and shorts and put on a white woolen dress, a traditional garment. “Tell me what I need to do”. We gave him instructions as he dressed his father’s wounds. Our words guided his hands while the Hogon’s severe eyes stared at us fixedly.

We gave him instructions as he dressed his father’s wounds, guiding his hands while the Hogon’s severe eyes stared at us.

We learned that the Hogon had never left his house throughout his whole life. He could go several months without washing or shaving. Nobody was allowed to touch him. His role as leader of the tribe was not hereditary, but chosen. That is what we understood, at least, from what we were told. It was impossible to be sure.

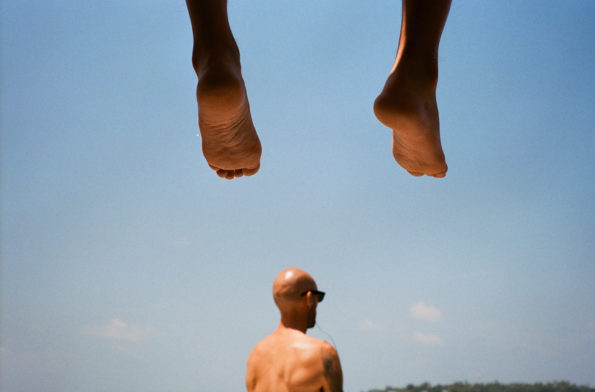

A story with no space and time

Every time I thought I was beginning to grasp some fact or ritual, someone else would give me a different version. I found it impossible to come to any conclusions, even after all the time I had spent with the Dogons. They live their own tale. There is no fixed reality. Something only exists when it exists in your story, in your mind. I think this is one of the greatest lessons I learned from this place.

It’s like living in a dream. Or sailing, sailing underwater.

There is no space, no time. No up, no down. There is no north, no south.

Without a written language, the Dogon interpret and explain their existence through stories, songs, artwork, and dance. Our idea of reality is physical and objective, but in the sub-sahara it felt like there were so many realities. Everything was so new to us, we couldn’t stop asking about the things around us: a ritual, a behavior, a building, or a dress. The answer was never the same; everyone had a version of his or her own. We were told many different stories, but they all seemed to make sense somehow. Our way of thinking didn’t hold up here: it didn’t give us access to their world. So we tried to surrender, get rid of our cartesian ideas, and embrace the multiplicity of voices.

It was an impenetrable yet fascinating fortress of tales and personal truths.

Photography. Antoni Arola

Words. Vincenzo Angileri

Watercolors, drawings and sketches. Antoni Arola

Thanks to Valerie Steenhaut and Júlia Rossinyol

Toni Arola

Designer & Artist

@antoniarolaestudi

@antoniarolaestudi