An African Folktale, Chapter III

In Utero

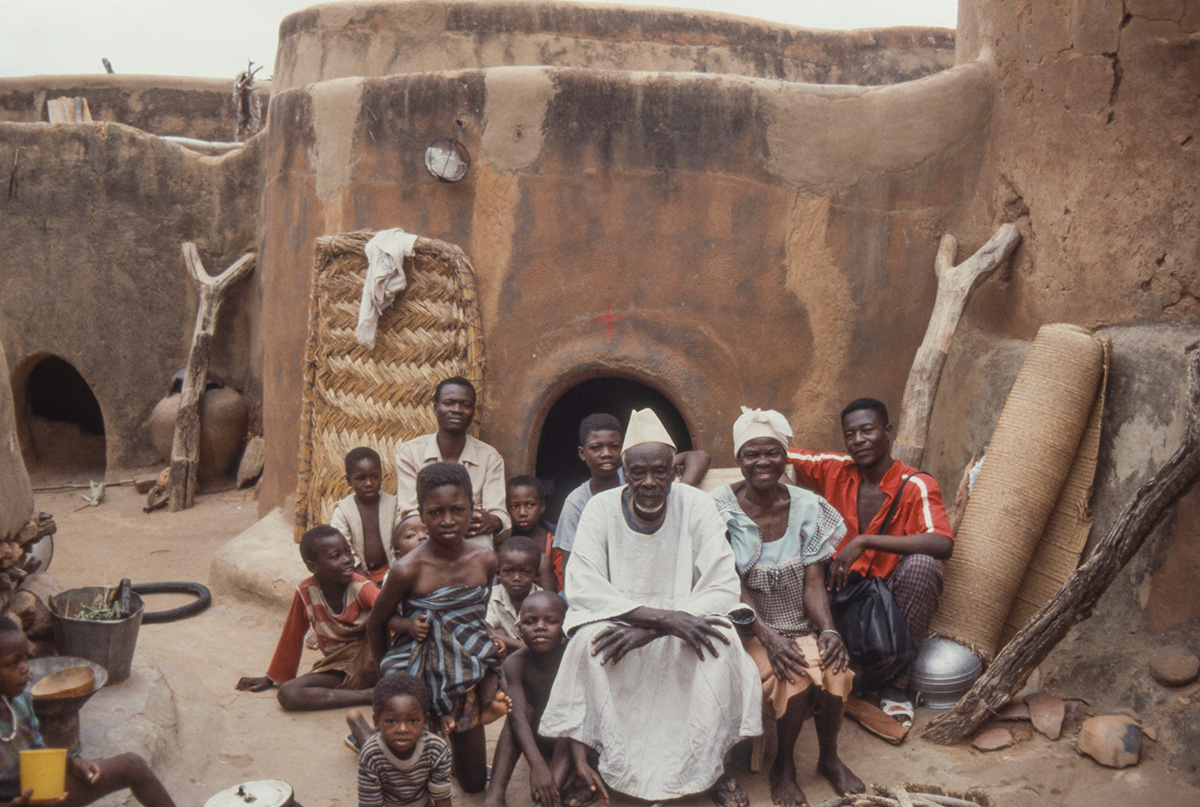

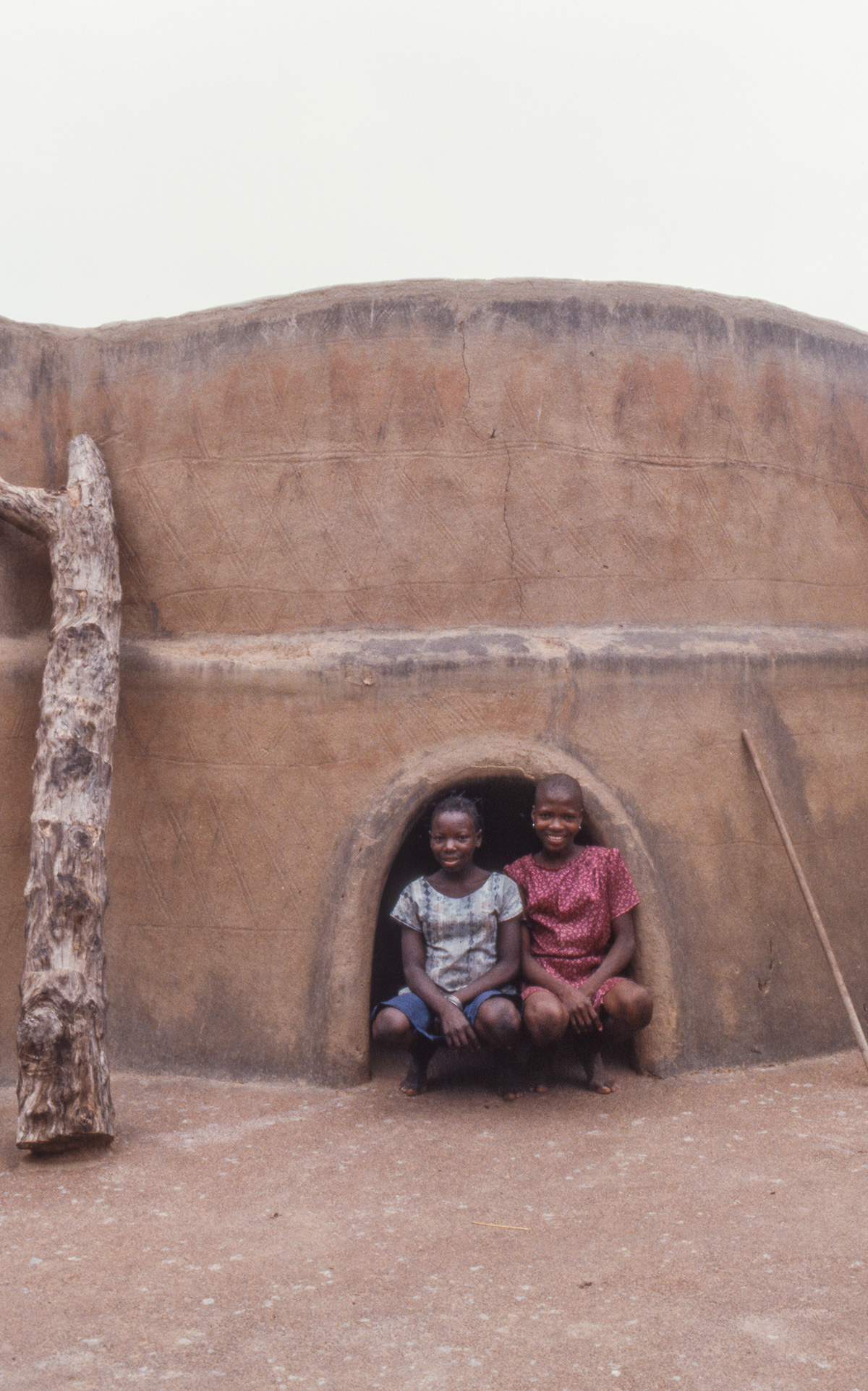

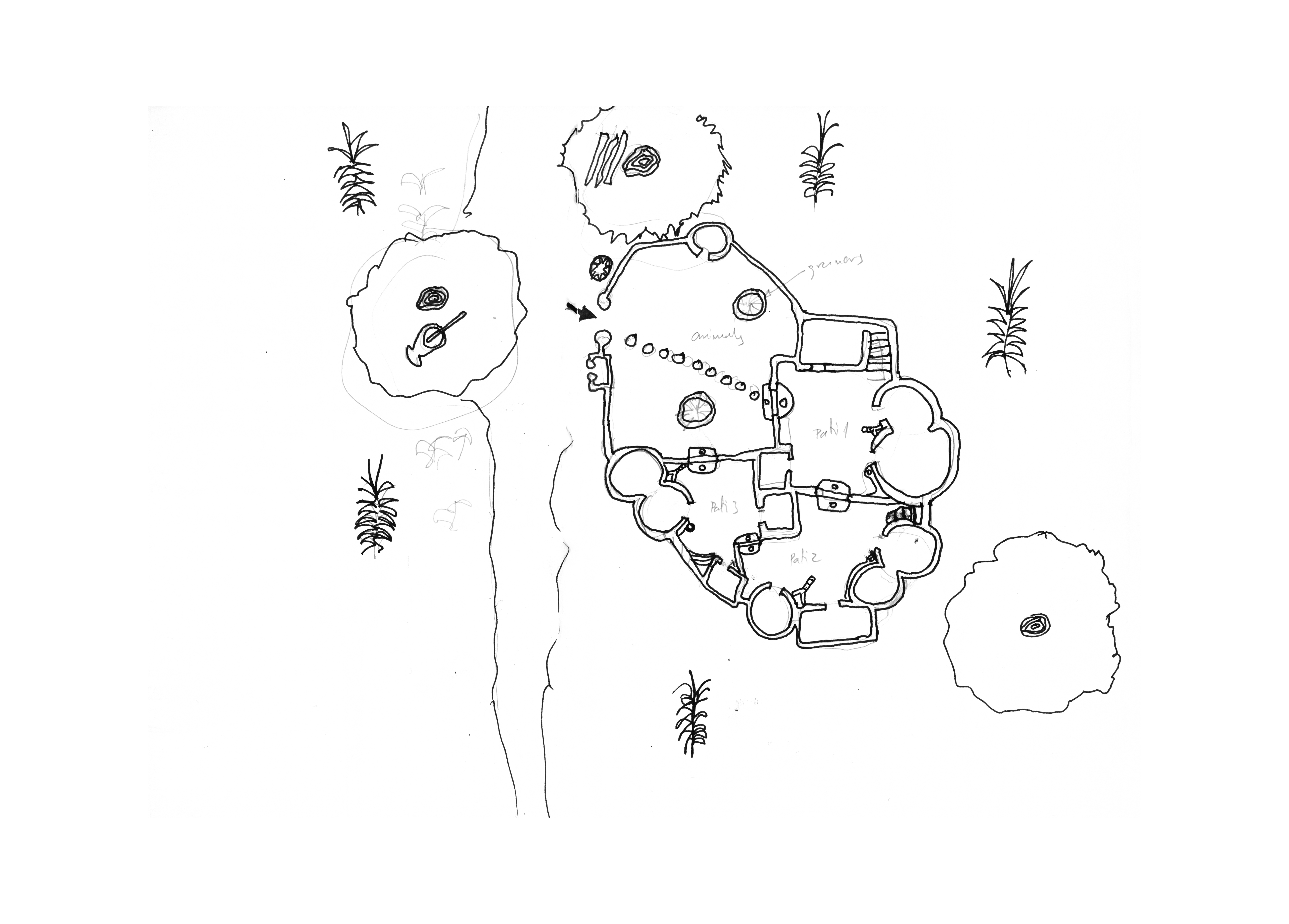

Entering a Gurunsi house meant entering a closed space filled with darkness. You had to get in on your knees. There were no windows, only a door and holes in the roof that they would cover and uncover when needed. The houses were rounded. The darkness felt warm, humanlike. Every family had its own its territory, their own patio. They spiralled into each other, creating a series of protective nuclei for the tribe.

The darkness felt warm, humanlike.

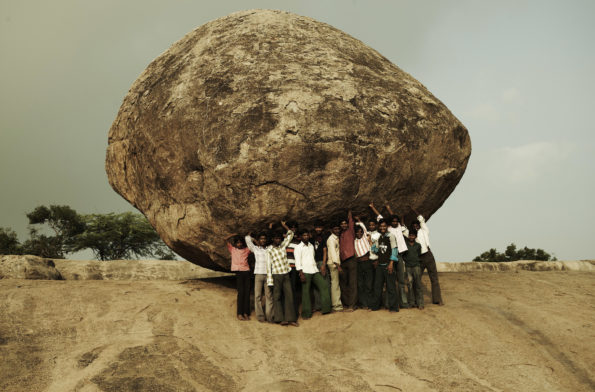

The architecture seemed to have some sort of algorithm generating a protective womb that reflected their conceptualisation of society. The walls both served as a way to divide space and to safeguard, protecting them from heavy flooding and livestock wandering too far off. Each patio recalled an utero, a womb. As if the Gurunsi were born into them to be nurtured there, to grow up in them until they became strong enough to climb its walls.

Like wombs, children would be born and wouldn’t leave the patio until they were strong enough.

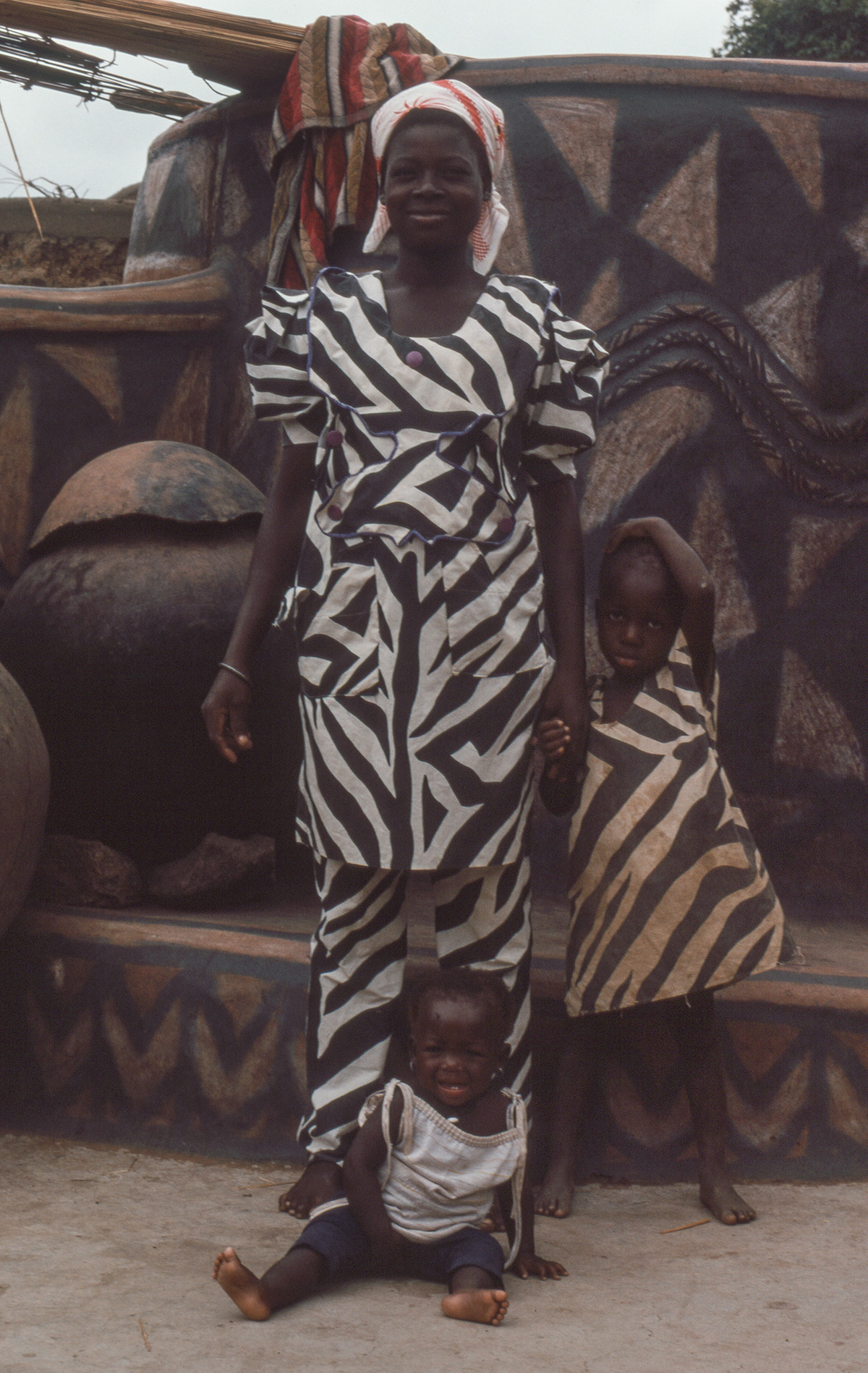

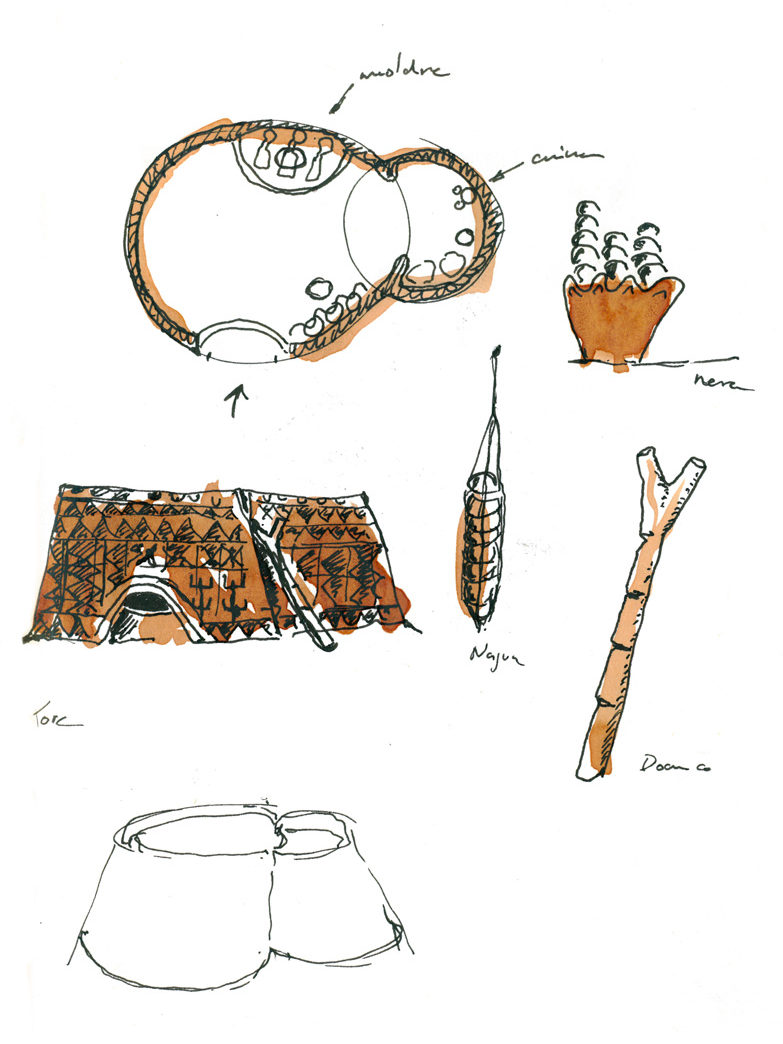

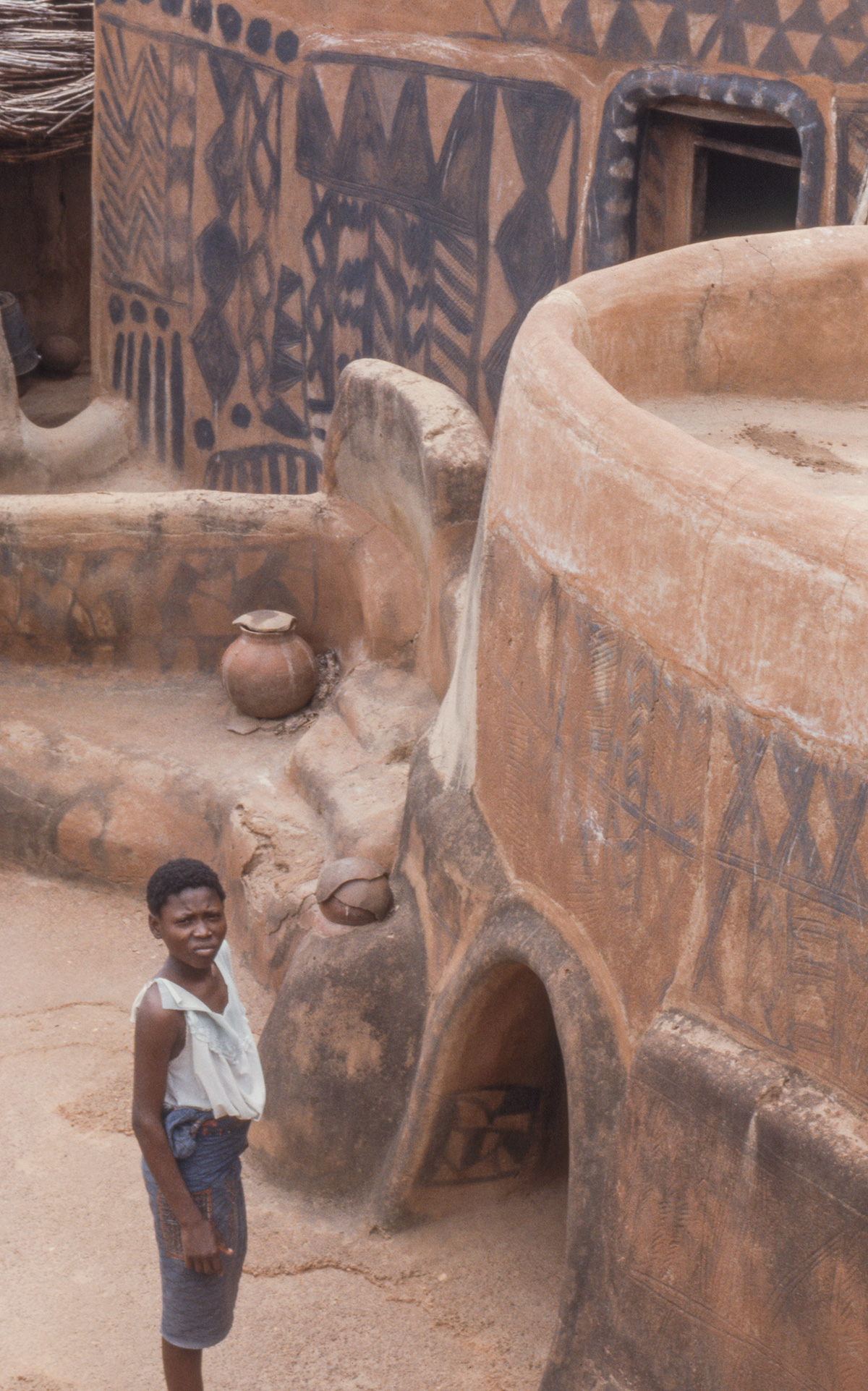

I saw a child crawling over one of these walls; his skin blended with the wall as if both made from the same material, the same land. The constructions seemed to follow the drawing of a fractal for the shapes looked like they were growing in a spiral. They were built right next to each other in a stream of houses, some bigger and some smaller, square when inhabited by men, rounded when nesting women and family. In contrast to the rough and rugged architecture of the Dogons and the Niger area, the mud here creates sinuous structures that feels gentle under your fingertips, serpentine in your hands, and flowing under your feet while you walk barefoot. You feel protected by the living and unwrinkled surface. Life here flows seamlessly, you forget you’re a guest and where you are. You just float, as if in a womb.

There was no element that didn’t feel unified with its surroundings.

Everything seemed connected.

Every wall of every house was painted with geometrical figures. I noticed how the base pattern kept on repeating itself everywhere we went, in a constant repetition of the triangle. It was everywhere; in the materials, the structures, the colours, the way one dresses and ties together his or her hair. Much like the Sub Saharan stories, they were never absolute, always ambiguous.

I was surprised how the pattern would sometimes change all of a sudden. Climbing up the stairs, its shape became so different. I learned that their ornamentation was an expression of the soul and personality of the one who had created it. Disoriented, clean lined; like an artistic expression I could never fully understand it in all its symbolism and function.

Photography. Antoni Arola

Words. Vincenzo Angileri

Watercolors, drawings and sketches. Antoni Arola

Thanks to Valerie Steenhaut and Júlia Rossinyol

Toni Arola

Designer & Artist

@antoniarolaestudi

@antoniarolaestudi