Down the Carretera Austral, Chapter I

A line through the wilderness

At the end of the 70’s, I was a kid living in Belgium, a country with one of the highest density of roads in the world. My father bought the break version of the Simca 1100 (a French car brand, today discontinued) and during summer holidays, he would happily drive more than one thousand kilometers by the famous Autoroute du Soleil to take the whole family to the south of France. It took us about ten hours. At the exact same moment, on the other side of the world, the only way to access the Chilean provinces of Aysen and Chiloe, covering a sixth of the country, was still limited to sea or air. An access complicated by the extreme weather conditions of the Patagonian Andes where during eight months of the year temperatures drop below freezing point and ten months out of the twelve it’s raining. Before the construction of the road, the lifestyle of the inhabitants of Southern Chile was based on auto-sufficiency and a sedentary lifestyle.

As a result, the region retains a spectacularly rugged, unspoiled environment and a strong unique identity.

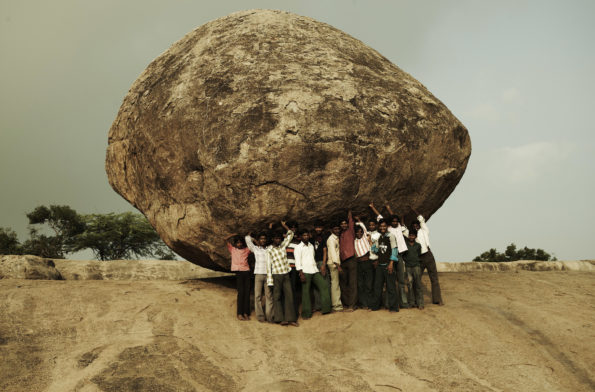

The construction of the Carretera Austral started in 1976 under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet and it took no less than 20 years, 10.000 soldiers and 300 million $US to achieve this titanic work of engineering. You can read the story in books and guides, but once you are on the Carretera, the history is a living being, right there, something that becomes part of your trip. During the first few years, the work conditions were inhumane as soldiers had three month shifts with only ten days of rest, a minimum salary, living in complete geographical isolation and sleeping in precarious campsites without basic services. Some of those campsites eventually remained and turned into villages, like Villa Santa Lucia, where I stopped for one night. Around 300 people live there today.

My idea for my three month trip through South America was to land in Buenos Aires, Argentina, go South to cycle the Chilean Patagonia, come back up North, cross Uruguay along the coast, reach Brazil and end up in Rio de Janeiro where I would take my return flight home. I didn’t want to plan much more than this. What was clear was that it was way too much distance to cover by bicycle in three months, so I decided I would not take my own bike from Europe.

If you want to have maximum freedom of movement, being dependent on an expensive personal piece of gear is something you will want to avoid. I thought about buying a bicycle in Chile and then selling it in Argentina. To be honest, that was a difficult decision, as it meant leaving more things to the unknown.

After two days of research and considering options such as second hand, I finally bought a new low-end mountain bike from José, owner of the only bikeshop in Puerto Montt. I managed to fit all my luggage without paniers, using my flattened backpack as an extension of my luggage rack. The two Ortlieb drybags I brought from Europe would do the rest. During the journey I met several bikepackers that were kind of surprised but also admirative about my minimal set-up. I actually completed the trip without any proper rain trousers. But this, I admit, was not a good idea at all.

In the oldest hotel of Hornopirén, a wooden building next to the bay, I met Gonzalo, a former engineer that told me about the numerous workers that died during the construction of the road. Works on the Carretera Austral have never ended. Scattered over its 1240 kilometers, heavy machines, trucks and working men are constantly maintaining the road, fighting against the forces of Nature. But not only is the road being maintained, it is also slowly being paved. Asphalt could technically be considered as a ‘natural-based’ material, as it actually consists of a mix of gravel and some semi-solid form of petroleum. Yet, the difference between a gravel road and an asphalted road is tremendous when it comes to the impact on the environment, and on the relation one can have with the Nature.

After the pavement, the life-style of the population living along the Carretera Austral will never be the same again. For better and for worse.

No doubt it’s probably not the asphalt in itself but everything that comes with it that affects our perception. The road signs, the safety equipment, the gas stations or other invasive infrastructures, the increased and fastest traffic, the littering and pollution are the ‘physical’ consequences. Additionally, the sudden accessibility to anyone at anytime, transforms an ‘adventure into a ‘casual touristic experience’. The accessibility of a place, no matter the beauty of it, somehow turns me off. I need that element of adventure and merit. That can sound like a selfish statement, as possibly, locals impatiently await for the road surface to boost local economy and quality of life. Should the beauties of nature exclusively be available for a few healthy privileged ‘adventurous’ people?

I’d rather spend two days hiking through a mountain to admire a more ordinary waterfall than take a car to observe the Niagara Falls.

In our Western mentality, we want to having everything under control and secured beforehand. But this time I said to myself: “The plan is that there is no plan”. It happened to be the best decision ever.

In the little village of Puyuhuapi, I met Veronica, a local veterinary that does health control in the salmon farms all along the coast. She drives thousands of kilometers a year to reach remote locations and for her, the paved road would cut the time spent in her car by half. Nevertheless, she also confessed to enjoying those moments driving her 4X4 across on the empty roads and wild landscapes. The day the road will be paved, it will never be the same again, and she will miss it. Veronica agreed to give me a ride during 30 kilometers in order to get me out of a section that was going to be closed for five hours due to the use of explosives. Without her, I wouldn’t have made it.

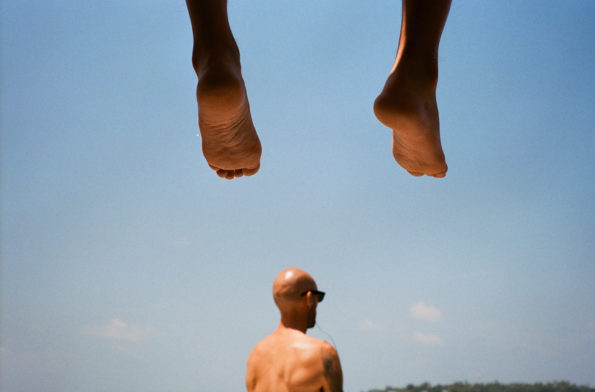

As I left Puerto Montt, I remember perfectly the incredible feeling of freedom and excitement, mixed with a bit of discomfort and anxiety to be alone on my bicycle. I was smiling alone.

The sensation of isolation and solitude on the Carretera Austral is enhanced by the fact that it is interrupted in three locations by waterways constraining travellers to take ferries that only operate twice a day. Once I disembarked the ferry and the few cars that were on board disappeared into the horizon, I remember feeling very lonely.

At first my head was filled with many negative thoughts as I started concerning about things like the absence of phone signal and eventual mechanical problems. But very soon I got used to it: anxiety transformed into a kind of euphoria mixed with strength that made me feel happy and, strangely, very much ‘in control’ of the whole situation. The main takeaway from all this is that too many times we are afraid of the unknown, invaded by negative thoughts, imagining everything that can turn out wrong. While, generally, things happen to turn out very well.

Photography. Jean-Marc Joseph Words. Jean-Marc Joseph Artwork. Àngela Palacios

Jean-Marc Joseph

Biker, Photographer and Filmmaker

@superjeanmarc

@superjeanmarc @superjeanmarc

@superjeanmarc