Kingdoms of Ice, Silver, and Salt, Chapter II

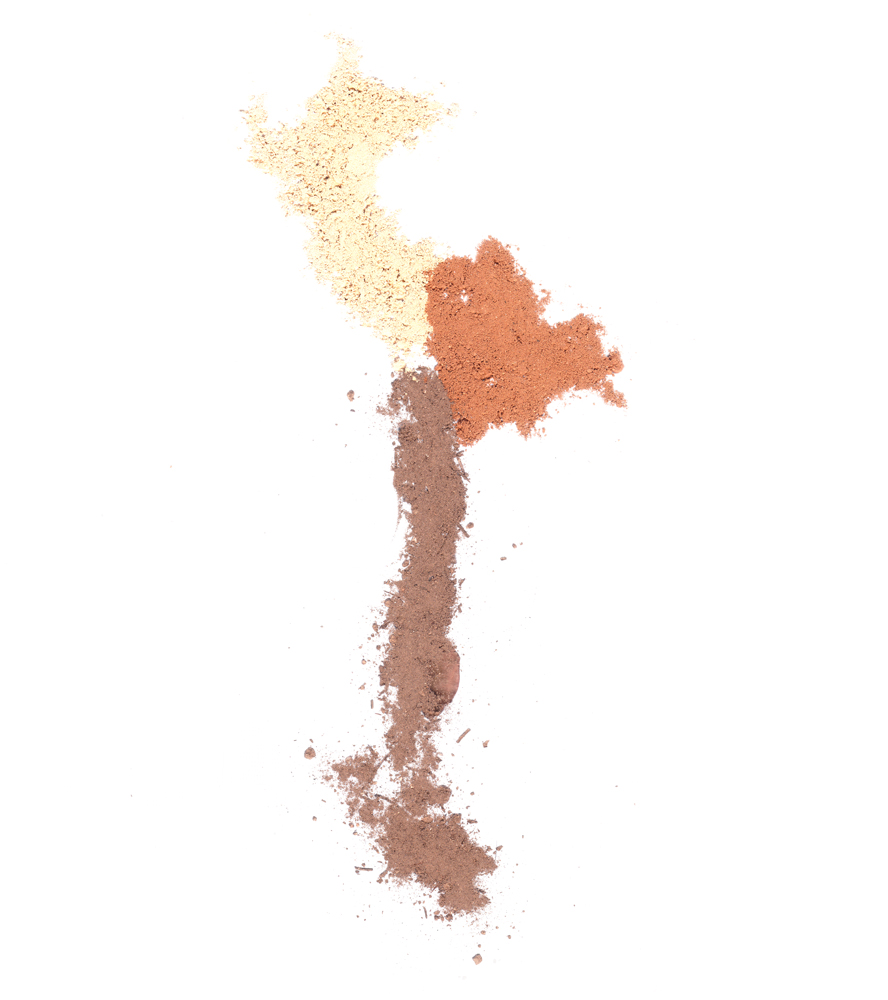

Silver

Bolivia, South America

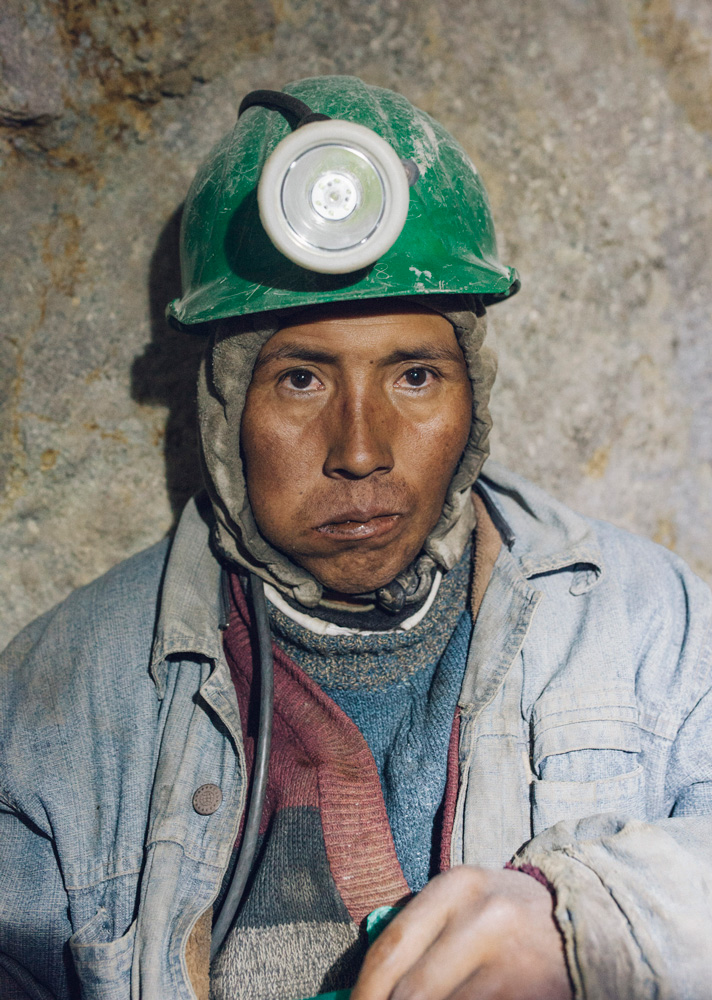

Working conditions are unhealthy. They drastically reduce the miner’s life expectancy and force them to leave the activity at the age 40. It’s a culture of survival; a reality that coexists with its exact opposite. Only by descending into its underworld does this precious metal become extractable. Only by descending the miners find the sustenance that will feed their families.

Death surrounds this mineral.

There is no way of understanding this place without understanding its past. People are aware that closing the mines would lead to a more dignified life but would also kill the soul of Potosí, erasing a legacy of over 470 years. To the people of Potosí, their history is both burden and necessity. The conflict is as deep as it is complex.

It seems as if this mineral is at the exact distance between life and death. Perhaps it’s why Potosians feel a deep respect for cemeteries. They consider them “life after the mines”, their true home.

Of the three minerals we are encountering throughout our long journey, silver is the only one that coexists alongside its people, the miners. We wanted to go back there to learn more. Descending the mines once more, we met a 70-year-old miner. He told us the mines had taken his wife and children. Because of that, it was only here, in the mines, where he felt at home the most. Perhaps by having spent half of his life in the mines his skin had ultimately mixed with the mountain.

In Cerro Rico, The Uncle is venerated as a God and it he is believed as the Lord of the underworld.

I am pretty sure when we left, I heard Georgina whisper to herself. She wondered if staying here too long made the lines between people and Earth to blur. Yet I’m not quite sure anymore if she really did or if I made it all up.

Photography. Anton Briansó

Words. Leticia Sala

Artwork. Ángela Palacios

Thanks to Georgina Morón y Antonio Fermia

Anton Briansó

Photographer

Georgina Morón

Pediatrician

@anton_brianso

@anton_brianso