Absent Kyrgyzstan, Chapter III

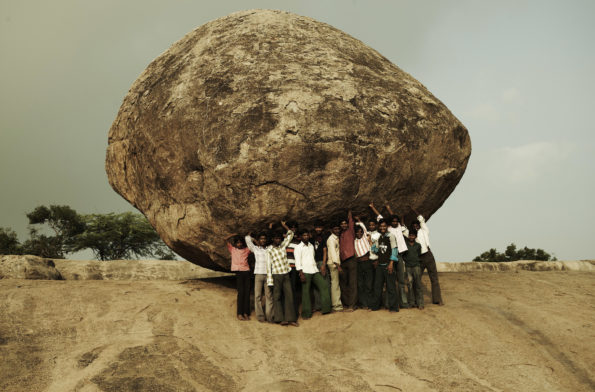

On Nomadism and the Unimportance of Space

Kyrgyzstan, Central Asia

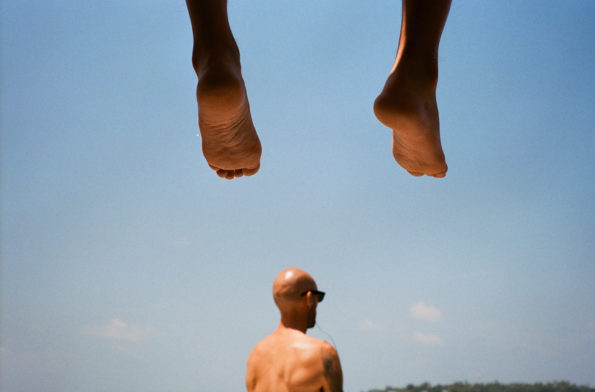

The modern-day nomad looks like someone who has embraced new possibilities to embark on an endless travel, the main driver being the need to satisfy a genuine curiosity. You see the nomads rushing back to nature, as if we’re collectively O.D.ing on concrete. I am part of the fortunate circle of people that has had the opportunity to live abroad for long periods of time, to have travelled extensively. When away, I was living out of a travel bag for months, once even over a year. Twenty kilograms of personal belongings summarising and defining who I am. I would pack and unpack them according to my next point of settlement.

I enjoyed it, of course, a lot. But I’m no real nomad. Not like the Kirghiz. It would be a self-lenient idea. I will always have a comfortable life somewhere I will always be welcomed back into after wandering. I believe knowing these displacements have an expiry date adds to the enjoyment of it; everything is up for taking, feelings are multiplied. And if it turns bad, well, it will all end eventually. Almost like a game.

Being a nomad, like the Kirghiz, is no game.

Whether things turn sour, whether you’re having a bad day, feel tired or sick, the moving doesn’t stop. Nomadism, as I could grasp it, appears to be amongst the most difficult lifestyles to embrace, being filled with external constraint. Today’s Kirghiz nomad life obviously differs from that of their ancestors; water-repellent canvases and cars were a great addendum, as well as the few spots the Kirghiz can ride down to to make a phone call, being, usually, in the city, where they have relatives.

Most nomads in Kyrgyzstan are half-nomads now. They move around during spring and summer in order to feed their cattle, but come closer to the cities and villages when the cold comes. They live less isolated lives than they used to, yet their everyday life is still strongly determined by the need to find food, if not for themselves directly, for the cattle they live off.

To me, nomadism is not solely about being free and being able to travel and settle wherever one pleases. It is a life that follows the chain of seasons; nature’s changing mood. It is a life in which survival is defined as a dependency of the elements. I can see beauty in it, I can understand the satisfaction one might get from it, but I don’t envy it. I’m an outdoorsy person, yet I don’t think I could take it for very long, unless there was no other option. Learning less and less people adopt the nomadic Kirghizstan lifestyle didn’t come as a shock. There is value in the comfort of a home.

Perhaps calling oneself a nomad has something to do with self-pride, as it calls upon an extensive imagery of hardship, heroism, and adventure. Through fantasy, it makes for a bigger experience. But it betrays the real heroism of the last people who still live this millennium-long lasting lifestyle, those who live a life of survival, perhaps not always by choice.

The modern-day nomad is perhaps the cosiest version of the nomad humankind has ever seen. He is free to embrace the best of both nomadism and settled lifestyle: the freedom and the comfort. That is how I feel at least, now that I have been granted to apprehend their world.

Photography and words. Céline Meunier

Map. Ángela Palacios

Celine Meunier

Photographer

@mcbinoculars

@mcbinoculars